The American Heart Association is planning to do a rolling cycle of focused updates. They started with the release of some small minor clarifications on recommendations they had made with the 2015 updates. In November of 2017 the first group of updates were released. As the 2017 updates are not a full guideline release, the most up-to-date are the 2015 guidelines, with included modifications of the 2017 focused updates.

There is not a 2018 CPR guideline focused update yet, but we’ll be sure to write about those if or when that occurs.

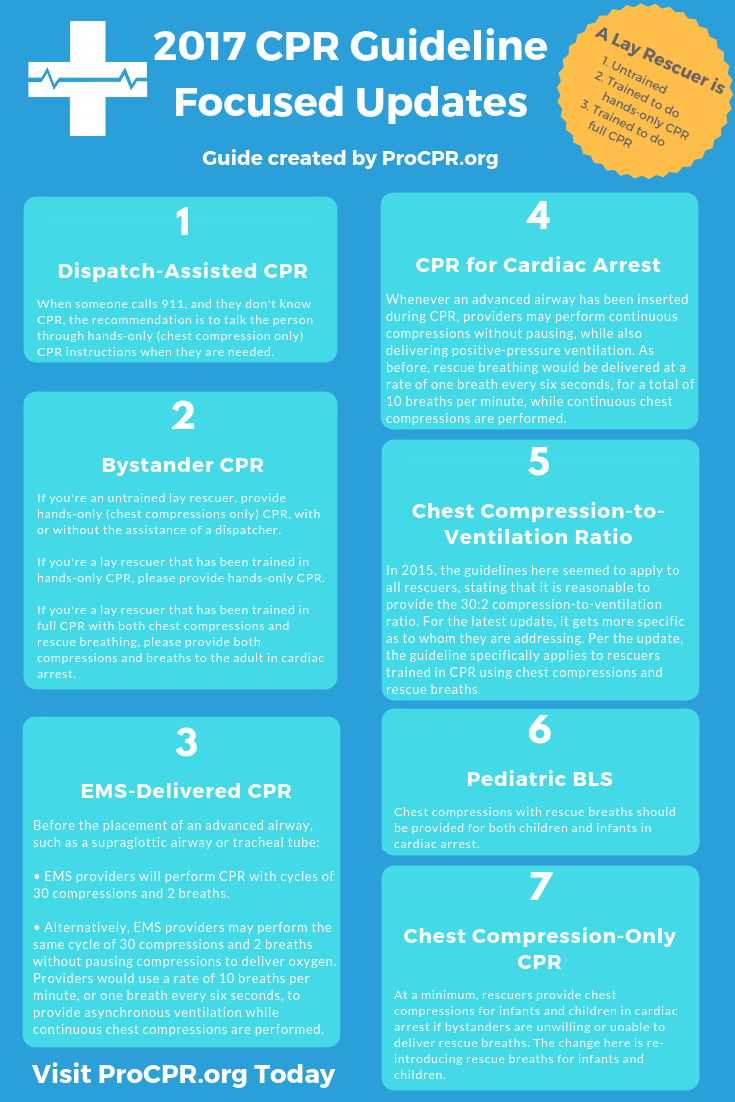

The 2017 CPR Guideline Focused Updates

There are 7 changes which include some clarifications on the descriptions of lay rescuers*.

-

Dispatch-Assisted CPR (for adults in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest)

When someone calls 911, and they don’t know CPR, they’ll often be directed on what to do over the phone by dispatch. Since chest compressions are pretty simple to teach verbally, the recommendation is to talk the person through hands-only (chest compression only) CPR instructions. Keep in mind that this is the recommendation for adults with a suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). The change from the 2015 guidelines is the addition to provide the instructions when they are needed.

-

Bystander CPR (for adults in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest)

If you’re an untrained lay rescuer, provide hands-only (chest compressions only) CPR, with or without the assistance of a dispatcher.

If you’re a lay rescuer that has been trained in hands-only CPR, please provide hands-only CPR.

If you’re a lay rescuer that has been trained in full CPR with both chest compressions and rescue breathing, please provide both compressions and breaths.

The change from 2015 is more clarification of what we had before, with the addition of the above recommendation for a lay-rescuer that has been trained in hands-only CPR.

It is important that all lay rescuers know that you don’t need to have taken a CPR class to be able to do chest compressions. A CPR certification card is not like a license to drive. It is meant to certify that you were taught a subject matter.

-

EMS-Delivered CPR (before placement of an advanced airway)

Before the placement of an advanced airway, such as a supraglottic airway or tracheal tube:

• EMS providers will perform CPR with cycles of 30 compressions and 2 breaths.

• Alternatively, EMS providers may perform the same cycle of 30 compressions and 2 breaths without pausing compressions to deliver oxygen. Providers would use a rate of 10 breaths per minute, or one breath every six seconds, to provide asynchronous ventilation while continuous chest compressions are performed.

These updates do not preclude the 2015 recommendation for EMS systems that have adopted bundles of care, that a reasonable alternative is the minimal interruption of chest compressions for witnessed, shockable, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

The change from 2015 is based on the use of interrupted vs continuous chest compressions when EMS providers performed CPR using both rescue breathing and chest compressions prior to placement of an advanced airway. The recommendation had been to pause between the cycles of 30 compressions to deliver two breaths, delivering each for one second.

-

CPR for Cardiac Arrest (when an advanced airway is inserted during CPR)

Whenever an advanced airway has been inserted during CPR, providers may perform continuous compressions without pausing, while also delivering positive-pressure ventilation. As before, rescue breathing would be delivered at a rate of one breath every six seconds, for a total of 10 breaths per minute, while continuous chest compressions are performed.

This change seems like more of a clarification in the language. The 2015 guidelines started out with rescuers no longer delivering the cycles of 30 compressions and 2 breaths (ie, no longer interrupting compressions to give those two breaths). It continued with the same recommendation of 10 breaths per minute while continuous chest compressions are performed. This change seems to clarify that CPR is not stopped, rather it is enhanced by the continuous chest compressions.

-

Chest Compression-to-Ventilation Ratio (for adults in cardiac arrest)

In 2015, the guidelines here seemed to apply to all rescuers, stating that it is reasonable to provide the 30:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio. For the latest update, it gets more specific as to whom they are addressing. Per the update, the guideline specifically applies to rescuers trained in CPR using chest compressions and rescue breaths.

-

Components of High-Quality CPR: Pediatric BLS (for infants and children in cardiac arrest)

Chest compressions with rescue breaths should be provided for both children and infants in cardiac arrest. Since the release of the 2015 guidelines, evidence has pointed toward providing full CPR with both chest compressions and rescue breaths. The old guideline wasn’t specific and only mentioned that conventional CPR should be provided for pediatric cardiac arrests.

-

Components of High-Quality CPR: Chest Compression-Only CPR (for infants and children)

The latest update recommends that, at a minimum, rescuers provide chest compressions for infants and children in cardiac arrest if bystanders are unwilling or unable to deliver rescue breaths. The change here is re-introducing rescue breaths for infants and children.

The 2015 guideline recommendation aligned the adult recommendation for hands-only CPR with the recommendation for children and infants, but the benefit of rescue breaths have justified a different recommendation for children and infants.

In other words, if you can provide rescue breaths alongside chest compressions for children and infants, do it. If you are unwilling or unable to provide rescue breaths, then at least do the chest compressions.

*A lay rescuer is described as someone that is:

- Untrained

- Trained to do hands-only CPR (doing only chest compressions)

- Trained to do full CPR including both chest compressions and rescue breathing

Here’s a PDF of the highlights from the AHA.